Almont North Dakota

1906 Centennial 2006

Eunice Klingensmith Evans has given me this information to post. The letter and history was sent to her Mother, Thelma Klingensmith (Hyde) in 1971. It is an unfinished history of Almont Ed Bond started to write years ago. It gives a stunning insight into the life and times in that area in the early days. It is our loss that he never finished it!

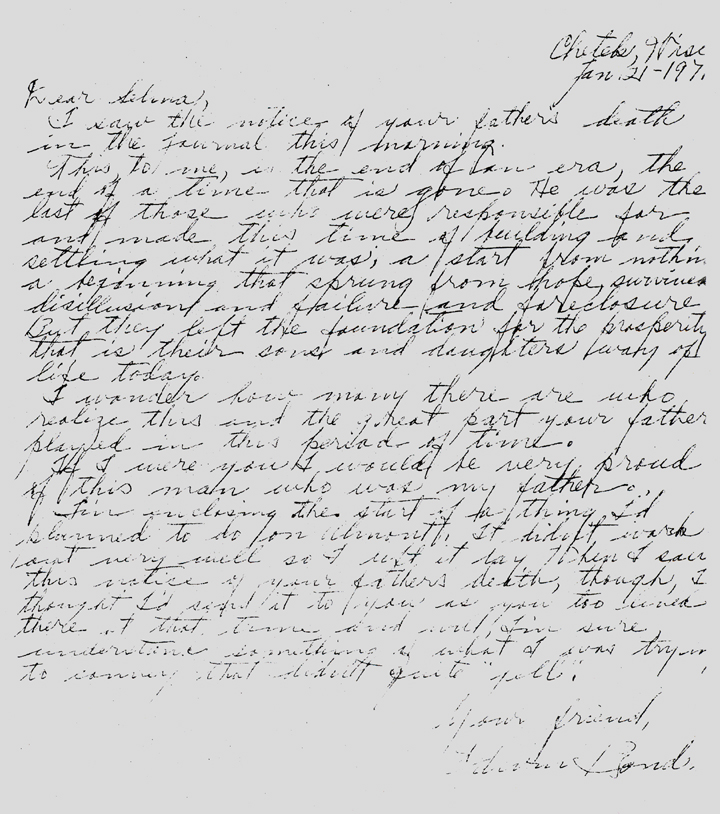

Chetek, Wisconsin

January 21, 1971

Dear Thelma,

I saw the

notice of your father’s death in the Journal his morning.

This, to me, is the end of an era, the end

of a time that is gone. He was the last of those who were responsible

for and made this time of building and settling what it was: a start from

nothing, a beginning that sprung from hope, survived disillusion and failure

and foreclosure. But they left the foundation for the prosperity

that is their sons and daughters way of life today.

I wonder how many there are who realize this

and the great part your father played in this period of time.

If I were you, I would be very proud of this

man who was my father.

I’m enclosing the start of a thing I’d

planned to do for Almont. It didn’t work our very well so I left it

lay. When I saw this notice of your father’s death, though,

I thought I’d send it to you as you too were there at that time, and

will, I’m sure, understand something of what I was trying to convey

that didn’t quite "jell".

Your friend,

Edwin Bond.

This is the story of a country that was settled and plowed and made over into the kind of a place the people thought it ought to be.

ALMONT

Where the Northern

Pacific railroad made a sashay through Rattlesnake Cut and pointed her

trains up the grassy flats of Curlew Valley; where cattle grazed knee

deep on the virgin prairie that had felt no hoof since the last buffalo;

here, in July of 1906, E.W. Hyde, an enterprising young man, decided

to build his town. Did he foresee, I wonder, a vast empire of

wheat or did he play a hunch? It was a big country. Wide open

it lay--waiting. He may not have read about “Making a stake

of all your earnings and cast it at one throw of pitch and toss” but

that’s what he did. It took guts and it took money. He

had the guts, he got the money and a town was born.

He was not the kind who has visions and sits

around meditating on them. On July 4th, the town was plotted and

the streets laid out. On the 15th, the first cars of lumber and equipment

were spotted on what the Northern Pacific called “Almont Siding” and

a busy place it was. A grain elevator raised it’s head high

over the prairies from where you could see for miles up or down the valley. It

was a beautiful view but disappointing if you were looking for fields of

grain. A lumber yard was built, a livery stable, hotel and restaurant.

A lot in Almont will cost you a hundred dollars.

A celebration is planned for August 12th,

and the first event is a church service held in the lumber shed. The

grass is trampled up and down the street, the grass that five weeks ago

waved in the wind like a field of grain. Did they know, these people,

did they stop to think what they were about to do to this country? What,

in turn, this country would do to them and all the families that would follow

because they were here and found it good? Beckoning letters to friends and

relatives with hopes and dreams in them and even some wishful thinking.

They came in droves, hungry for land and the

security that was, somehow, associated with it. Pitifully unaware of the

caprice of a semi-arid land where every spring was a mirage of hope. Where

every plan, every dream must run the gauntlet of drouth, wind, rust or hail. The

newly broken sod, nourished and fabricated by the grass mulch of centuries,

brought forth an abundance that fulfilled all but the wildest dreams. Almont

was a lusty, brawling town of boom and prosperity with a contributing territory

reaching about as far as a man wanted to travel with a team. Building

went on at a pace limited only by the availability of lumber and carpenters. The

lumber came from Mr. Hyde’s lumber yard. The largest submitting

territory lay to the south and drew grain from as far as the South Dakota

line. Teams and wagons were waiting in lines a mile long to sell

their grain to the only available facility; Mr. Hyde’s elevator.

Mr. Hyde was doing well. Mr. Hyde was

prospering from a formula that succeeds only if you can follow the directions. You

must be able to see a bit further ahead of your nose then the average citizen. You

still can’t see the whole picture but you can imagine the rest. The

next requirement is to sell the idea to someone with a lot of money. The

last and by far the most dangerous ingredient is the process of dumping

the entire aggregate into one pot, namely: the work of lifetime up to this

point; your reputation as a business man and a good guesser in addition

to all the money you have and all you can borrow. Mr. Hyde’s

success was a big success but it didn’t just happen. He worked,

he planned, he walked a dangerous mile but it seemed, at the time, that

he was one of those lucky fellows who just happened to be in the right place

at the right time.

The cattle moved back into the hills. The

big cow spreads, and the small ones too, run on the open range. No

grant had they nor title. Free and open the land lay far beyond the horizons

and they could not believe it would not always be so.

The Krites brothers, George and Charley, rode

for the big spreads. Years of sweating it out in the hay camps, hard

long hours in the saddle, freezing through the rugged winters. They

who survived were men who backed down for no one. Hard as nails, they could

stand up and be counted. At last, their dream realized, they managed

a small cow spread of their own. The cow sense, the know how, they

had learned the hard way. They would grow with good management and

hard work. Their brand would prosper and run wide. They’d

need help but then they could afford it, maybe back off a bit from some

of the hardest work, they weren’t so young any more. But that

was a dream. That, with luck and hard work, lay ahead. Now spring

calving was in full swing and they rode from early till late. One

morning they topped a hill that gave them a view for miles and what they

saw amounted to Hyde’s dream come true and their own shattered.

The land was swarming with people. Teams

and wagons, some covered, some open, loaded and hanging with every imaginable

belonging from pots to plows they scurried around like ants staking their

claims, throwing up a shelter for the family and heading back for another

load from their emigrant car that waited on the Northern Pacific siding.

The teams sweat and strained and the sod slid in black ribbons off the plows. The

sod house went up apace and the men and teams headed for the timbered brakes

and creeks. The trees, sparse in this land of prairies, fell to the eager

axes and the wagons creaked and groaned out of the coulees with posts and

fuel. Smoke curled from the chimneys and fence posts marched down

the section lines. Bright new wire, deadly with barbs and taut as

a fiddle string.

The grass, the prairie, beautiful as God made

it; mulching, grinding, covering the naked earth. Where flowers may

grow or a rabbit hide. Where Meadow Lark and Prairie Chicken nest

deep and safe. The grass, bending and billowing where the wind walks,

following the meandering stream in all it’s turnings, climbing the

rugged slopes far up on the buttes. But a new way of life is here. The

old is gone. It left with the grass and it will not return. It will

change the people, the country, the customs and even some of the laws. It’s

name is wheat.

Few places there are where man may harvest

year after year without replenishing the soil. The prairie gives

and continues to give asking only that enough of it’s grass cover

be left for mulch to nourish and protect it’s rooted sod. The

hungry roots of seeded grain crop quickly depletes it’s stored up

nutrients and prosperity waned as the last surge of nourishment was drained

from the thin ribbons of sod. The thing was done. The land

turned “wrong side up” parched and burned in the pitiless sun,

stirred and shifted in the wind and at last with nothing to hold it rose

in angry, black clouds that scourged the earth. A country to test

a man, but these emigrant cars that were kicked off on the railroad sidings

brought a breed of men who didn’t stampede easily. They cussed

the country and the fate that brought them here. They and their families

suffered hardship and want to hold the inadequate 160 acres of homestead

land. One by one they lost them by way of drouth, hail and 12% interest

but they stayed and eked out a living on the railroad, the “Sims Coal

Mine”, or the “Riverside Cattle Ranch” where the living

wage was $1.00 to $1.25 per day. A hard country but it drew a breed

that surpassed and finally conquered disappointment, disaster and whatever

evil must befall an unfortunate race who dare to destroy it’s virgin

beauty and purpose.

My father, Wallace bond, was definitely one

of this race. They are an adventuresome sort who are convinced beyond

reason that there is a “Utopia” and that they have discovered

it. They regard anyone who cannot realize this with tolerant impatience

or even suspicion. This is the hardy fellow who, in books and pictures,

arrives at the outer edge of nowhere with his trusty plow and his frightened

wife. Takes on drouth and hail, fire and windstorm, conquering all. He

has become a romantic legend, this over-rated apostle of hope, this wishful

dreamer who is willing, anxious, to trade whatever he has of goods and comforts

for some place where the troubles he now has do not exist. He is

the picture we cherish of the spirit of daring and of freedom. The

epitome of rugged manhood--the pioneer. True, he forged ahead into

he raw edge of death and calamity from the Atlantic to the Pacific. He

was, taken as a whole, as an elemental force in history, a hero and an asset

to the country, namely: to the wiser ones who followed along behind profiting

from his misery. It is an urge, a drive, this pioneer spirit that

is present in certain family lines. A trait or, even worse, a heritage.

Wallace Bond, from the vantage point of his

emigrant car viewed the thriving town of Almont, No. Dak. huddled on the

flats of Curlew Valley just north and west of the convergence of Sims and

Curlew creeks. It was now, in April of 1912 a thriving town six years

of age. He’d left a beautiful town in Iowa, a good business,

a home the like of which he’d never enjoy again and a sizable piece

of money. He had bought a section of land ten miles south of town

that was clear and paid for. Standing in the open door of his emigrant

car he looked it over with a glint in his eye and, for some unknown and

unfathomable reason, knew that he was right where he wanted to be. You

see he was a pioneer.

His ancestors came (fled, no doubt) from Wales,

England. Killed their quota of Englishmen in the revolution and started

looking westward, wondering what lay beyond those mountains. Two

generations later found his (Wallace Bond’s) family in the vicinity

of what is now Willmar Minnesota (he was still an infant) fleeing from the

outraged Sioux in a covered wagon attached, of all things, to a team of

oxen. They miraculously escaped but two years later when the offending Indians

had been run off they returned to their ravaged homestead and begun life

anew. This included the almost unprecedented achievement of rearing five

pairs of twins along with several unexplainable singles to a grand total

of fourteen children. At this point Corodon Bond, Wallace Bond's father

and the head of the family, died.

At this time, according to family tradition,

they would, no doubt, have pulled stakes and headed for the Rocky Mountains

but with so large a family and with my father, Wallace Bond, only fourteen

years old, the oldest child, it was deemed advisable to abandon the westward

ho idea for the time and retreat backwards to Iowa where lived some less

adventurous relatives who had offered to help in this difficult situation.

Now, forty years later at the age of 54, Wallace Bond loaded what of

his possessions he considered most advantageous in a new country. The

last item was a team of horses with the necessary hay and grain and

a tub for water. The car was the property of the Great Western

railroad and was loaded at Belmond Iowa. All went well until

the final procedure; the billing out of the car. The destination

was the problem due to the fact that Almont, No. Dakota simply did not

exist. The agent wired the division point. They were able to

locate a Mandan, a New Salem and a Sims but no Almont. If indeed

there was some such outpost it would be on the Northern Pacific railroad. As

a last resort a wire was dispatched to the Northern Pacific headquarters

in Minneapolis and the information came flashing back over the wires

that their records listed an Almont siding beyond the city of Sims and

to this doubtful destination the car was billed.

I relate this brief history of my father,

Wallace Bond, to avoid any confusion that might occur when I stated that “from

an open door of his emigrant car he looked it (Almont) over with a glint

in his eye and knew that was where he wanted to be.” The

grass covered hills bordered the valley. The land stretched on and

on beyond the farthest hills. The air was light and dry and the wind blew

free. Here was the start of things. Here was the beginnings of whatever

would befall this country. He was here and the blood of his restless

forbears told him here was where he belonged.